– Helen Grant became actively involved in politics in 2006 and was elected as Member of Parliament for the Kent constituency of Maidstone & The Weald at the 2010 General Election.

Helen was Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Sport and Civil Society from October 2013 to March 2015. She was Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Minister for the Courts and Victims and Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Women and Equalities from September 2012 to October 2013.

In January 2021 Grant was appointed as the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education, leading the UK’s efforts internationally to ensure all girls get 12 years of quality education. One of her goals is to drive a global campaign to improve learning and get 40 million more girls into school around the world by 2025. Helen is also the Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy to Nigeria.

ECW: Why is the UK putting girls’ education at the top of its international development agenda and where does education in emergencies and protracted crises fit into this?

Helen Grant: Achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 – realizing the right to quality education for all by 2030 – is a major priority for the UK government. We have particularly focused on girls’ education not only because girls are more likely than boys to miss out on education but also because it is a particularly powerful investment that can create healthier societies, increase per capita GDP and reduce violence. The UK used its G7 presidency to ask G7 leaders and other partners to sign up to ambitious targets of 40 million more girls in school and 20 million more reading by the end of primary school, by 2026. We also published our Girls’ Education Action Plan that sets out our roadmap to achieving these targets.

However, we will not deliver education for all without reaching children affected by crisis. We know that children in fragile and conflict-affected countries are more than twice as likely to be out of school compared with those in countries not affected by conflict[1]. This is particularly acute for girls; current trends also show that girls are particularly affected and will not reach 100% lower secondary completion in crisis-affected countries until at least 2063[2].

That is why education in emergencies and protracted crises is a priority for the UK. It is also why I am proud that the UK is a founding member and the current largest donor to Education Cannot Wait

ECW: The climate crisis is an education crisis, especially for girls. Through the UK’s leadership of the November climate talks (COP26), new efforts are being taken to bring together actors and connect the dots between education, climate change and humanitarian relief. Why is connecting the dots so important for achievement of the SDGs and Paris Agreement targets, especially between girls’ education and climate action?

Helen Grant: Globally, at least 200 million adolescent girls are currently living on the frontline of climate crisis as they belong to the poorest households in the poorest areas and are therefore most vulnerable to the negative impacts. We also know that extreme weather events are becoming more frequent and severe, disrupting the education of nearly 40 million children a year. As climate shocks become more frequent and severe, disrupting the education of millions of children, we will need a fully resourced and effective emergency response to provide protection and keep children learning.

It is so important to connect all of these dots as educating girls can make a huge difference in addressing climate change and its impact. When girls go to school, they and their families can cope better with severe weather events. Education also allows girls and women to participate much more in decisions and leadership in relation to climate resilience, adaption, and mitigation.

This is why the UK is committed to action and at COP26 we launched a wide-ranging consultation to guide the UK’s future work on these critical issues. We want to listen and learn from all involved, from young people affected by this crisis as well as teachers and civil society organisations. As the UK Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education, I am personally committed to highlighting the links between climate change and girls’ education and will continue to do so in 2022 and beyond.

ECW: In January 2021 you were appointed as the UK Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education, leading the UK’s efforts internationally to ensure all girls get 12 years of quality education. For the UK, and yourself personally, why is it crucial that we invest in girls’ education now in emergencies & protracted crises? What can be done to accelerate efforts to achieve equitable, inclusive education by 2030?

Helen Grant: I am hugely honoured to be the Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Girls’ Education. In this role I globally champion the message that providing every girl on the planet with 12 years of quality education is one of the best ways of tackling many of the problems facing the world today such as poverty, climate change and inequality.

It is crucial to invest in girl’s education in crisis affected countries; only 27% of refugee girls are enrolled in secondary schools and 20 million girls are at risk of dropping out in the next year due to conflict and crisis[3]. Out-of-school girls are at greater risk of violence, sexual abuse, early and forced marriage and human trafficking. All of this creates a very real risk of a lost generation of girls.

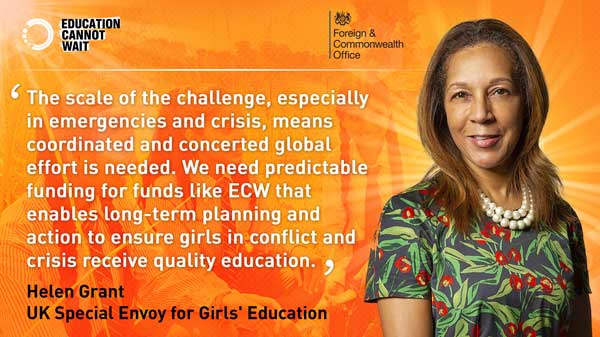

The scale of the challenge, especially in emergencies and crisis, means that coordinated and concerted global effort is needed. Specifically, we need predictable funding for funds like ECW that enables long-term planning and action to ensure girls in conflict and crisis receive quality education. We also need high-quality and sustainable interventions which means ensuring a comprehensive package of support that moves away from simply providing textbooks but includes a focus on learning, protection and the wellbeing of children and school staff.

ECW: An estimated 4.2 million children are out of school in Afghanistan, including 2.2 million girls. What are the UK’s plans for girls’ education in Afghanistan?

Helen Grant: Education has been at the heart of Afghanistan’s development gains of the last 20 years, helping to transform women’s role in society and push back poverty. We must ensure that Afghanistan’s education systems are operational as soon as possible. This includes opening secondary schools and other education spaces for girls so that they can continue to access 12 years of quality education; and ensuring that schools are protected as safe places.?It is also imperative that female teachers are able to work safely and without barriers.

The UK is working with international partners to help coordinate the education response in Afghanistan. I’m proud that ECW was able to swiftly stand up a First Emergency Response for Afghanistan to support internally displaced children which will reach 38000 children with temporary learning.

ECW: As a member of the UK Parliament, a mother of two and a lawyer, how can education secure other basic human rights for children and adolescents, especially for girls, who are among those left furthest behind and vulnerable in emergencies and protracted crises?

Helen Grant: Investing in girls’ education is a game changer. A child of a mother who can read is 50% more likely to live beyond the age of 5 years, twice as likely to attend school themselves, and 50% more likely to be immunised. Girls who are educated are more able to choose if, when, and how many children they have. Education also opens up employment opportunities for girls, helping to lift them and their families out of extreme poverty. Girls’ education is therefore vital to women and girls, but also in levelling-up society, boosting incomes and developing economies and nations.

These benefits are just as important, if not more so, for girls in emergencies and protracted crises. Quality education can also provide much needed practical knowledge and physical and psychological protection to girls and boys. Lastly, the evidence shows us that girls’ education can also decrease the likelihood of conflict and increase resilience to climate disasters – as such, education is a critical pillar in reducing the risk of future crises.

ECW: From your leadership vantage point, how can investments in education benefit the global economy, improve peace and security and help us build back better from the triple-C crisis threats of conflict, climate change and COVID-19?

Helen Grant: Even before the COVID-19 pandemic the world was facing a learning crisis. Tragically the pandemic has now become the largest disruptor of education in modern history, affecting 1.6 billion children and young people at the height of the pandemic. Without remedial support, a further 72 million children may fall behind. Children living in emergency and protracted crises affected countries are at particular risk; not only they are more likely to be out of school already, but they are also more vulnerable to threats such as food insecurity, climate change shocks and violence which we know can disrupt education further.

Getting all children into quality education is critical if we are to avoid undoing the global gains of the last two decades. Educating children is also key to breaking the cycle of conflict that exists in many countries in the world, with each year of education reduces the risk of conflict by around 20%. Finally, it can also help build children’s future resilience to climate change shocks. As such, education not only helps children today but protects the children of the future by supporting more peaceful and resilience societies.

Missing out on school has long-term consequences not only for individual children’s life prospects but also the prospects of nations. We must reopen schools as soon as possible to tackle the global learning crisis and protect children’s futures.

ECW: Our readers would like to know you a little better on a personal level and reading is a key component of education. Could you please share with us two or three books that have influenced you the most personally and/or professionally, and why you’d recommend them to other people to read?

Helen Grant: There is just one book that I would like to mention, which is Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngosi Adichie.

It is a novel set in the country of my father’s birth – Nigeria. And with an English mother, I’m extremely proud of both my British heritage and Nigerian heritage. I love visiting Africa.

The book touches on domestic violence, religious oppression and coming of age in a fast-changing country. I was a family lawyer for 23 years prior to politics, specialising in domestic violence and child abuse work. The writer has covered these issues with great subtlety and sensitivity. In addition to the physical suffering, it shows so clearly how violence and abuse crushes self-confidence and self-esteem in victims, wrecks families and ruins lives.

I recommend the book to others and will read it again myself for sure.

[1] GEM Report, Policy Paper 21, June 2015, p.2.

[2] INEE Mind the Gap Report – 2021

[3] INEE Mind the Gap Report – 2021